Here is my testimony from last night’s CEC 15/CEC 13 joint meeting about state testing.

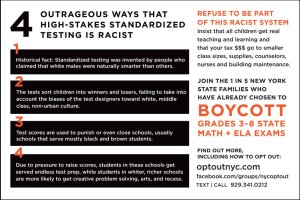

I am here tonight as both a District 15 parent of a third grader and as a District 15 ENL/ESL elementary school teacher. Luckily as a parent, my daughter is in a school where the vast majority of students opt out and there is no test prep. However, as a teacher this is the hardest time of year for me. One reason I speak out against the Common Core-aligned state testing program is because it helps me to live with myself as a teacher who is forced to administer the math, English-language arts (ELA) and NYSESLAT (New York State English as a Second Language Achievement Test) assessments each spring- one after the other. I watch kids suffer and shut down, and there’s nothing I can do about it. As a veteran teacher, I feel like a fraud, complicit in perpetuating an educationally unsound and racist testing program that is designed to harm, not help, our public schools. Common Core state testing is at the heart of corporate education reform. It’s the tool, the weapon, being used to privatize public education and dismantle teacher unions.

To me, the test scores aren’t legitimate because they come from highly flawed assessments. Any feedback I get from the testing company is unreliable because of the tests’ poor design, developmentally inappropriate content and ever-changing cut scores. However, authentic and meaningful classroom work, created by educators, not testing companies, paints a much more accurate picture of student progress. Furthermore, Common Core curriculum that prepares students for these tests is not innovative or transformative. Its pedagogy is anti-democratic (see Nicholas Tampio’s critique of Common Core), and it’s highly scripted and formulaic. Context and real critical thinking are lacking, and the work itself is tedious. English-language arts, for example, relies heavily on excessive close reading.

Test scores also hinder school integration efforts. Real estate agents use schools with high test scores to lure buyers and renters to certain neighborhoods. Some affluent families in gentrifying neighborhoods use test scores to justify their rejection of schools whose students are largely Black, Brown and poor. By design, test scores are used to unfairly label schools, students and teachers as “failing,” and they are used to close local schools in Black, Brown and poor neighborhoods. This destabilizes communities and adds stress to the lives of families living there. This focus on raising test scores also takes us away from the messy – but URGENT – work we must do to address school inequity and segregation. According to civil rights investigative journalist and District 13 parent, Nikole Hannah-Jones, the thinking is: “if we can just get the test scores up we don’t have to do anything about the fundamental inequality of segregated schools.” She also shared that her daughter is doing great in her low test score District 13 public school arguing that, “the scores aren’t even reflecting what’s being taught in that school.” Nikole Hannah-Jones spoke at the Network for Public Education’s annual conference in Oakland, CA last October. I encourage you to listen to her entire speech.

As we all know, there are two school systems in New York City. Hannah-Jones calls this disparity “desperate,” and she’s cried over it. So have I. So educationally unsound is Common Core test-centric schooling that I felt like I had no choice but to leave my beloved Title I school in East New York, my second home where I spent my first nine years as a teacher. I am now in a District 15 school with high test scores and the differences between the two are striking.

NYC schools with low test scores face immense pressure to raise scores and therefore most decision-making revolves around this goal. No one wants to be on a focus school list, which results in greater scrutiny. Teacher morale in these schools is low and this trickles down to students. Ask your child’s teachers how truly happy they are. The schools are top-down and undemocratic and the staff is micromanaged. There is little to no freedom to teach and learn in schools with low test scores. Schools with low test scores are constantly changing reading, writing and math programs, and they aren’t teacher-created or even teacher-selected. Schools with low test scores are pressured by districts to adopt developmentally inappropriate and uninspiring test prep curriculum such as Pearson’s ReadyGEN. Pearson, as you may know, created the first batch of Common Core-aligned ELA and math assessments. In schools with low test scores, skills-based test prep begins in kindergarten, which completely disregards early childhood studies showing that “the average age at which children learn to read independently is 6.5 years” (Defending the Early Years).

In many schools with low test scores, there’s an almost heart-stopping sense of urgency to improve students’ performance in math, reading and writing. As a result, these schools have limited choice time and no free play in the lower grades. Any type of play must have a literacy skill attached to it. There are fewer field trips, fewer enrichment programs and fewer (if any at all) school performances. An inordinate amount of planning and organizing time is devoted to preparing for the state tests. Out-of-classroom teachers are pulled from their regular teaching program to administer and score the tests. Countless hours are spent bubbling testing grids. In 2013, as an out-of-classroom ESL teacher, I lost 40 days of teaching to support this massive testing operation.

English-language learners (ELLs) are the most over-tested students in New York State and very few people – including educators – ever set eyes on the NYSESLAT, the annual ESL assessment given to English-language learners every spring following the state ELA and math tests. In fact, many parents of ELLs don’t even know their child is taking it. The NYSESLAT is arguably worse than the ELA test, and it is comprised of four testing sessions, which means four days of testing. The kindergarten NYSESLAT has 57 questions. The reading passages are largely non-fiction, and some of the topics are obscure, outside of the students’ everyday life experiences. The NYSESLAT is more of a content assessment rather than a true language test. It’s also excessive in its use of close reading. The listening section, for example, requires students to listen to passage excerpts over and over again. Testing at the proficiency level is the primary way an ELL can exit the ESL program. I have students, already overburdened by state testing, that will remain at the advanced (expanding) level on the NYSESLAT because they don’t score well on standardized tests. Like the Common Core ELA test, the results of the NYSESLAT tell me nothing about what my students know.

Is this the type of schooling our communities want? I can tell you that educators by and large reject this top-down, one-size-fits-all, corporatization of public education. Shouldn’t community input be taken seriously? What is OUR definition of equity and excellence? Does it include high-stakes testing? The Journey for Justice Alliance offers a vision for sustainable community schools in low-income, Black and Brown neighborhoods throughout the United States: relevant, rigorous and engaging curriculum that allows students to learn in different ways, project-based assessments, supports for high quality teachers, smaller class sizes and teacher aides, appropriate wraparound support for students, including opportunities for inspiration and access to things students care about, a student-centered school climate, quality restorative practices and student leadership opportunities, transformative parent engagement, and inclusive school leadership which considers content knowledge and community knowledge (Jitu Brown, North Dakota Study Group’s annual conference, Tougaloo College, Jackson, MS, 2/16/18). As Camden, NJ organizer Ronsha Dickerson put it, “We want what we need, not what you want to give us.” This, to her, is real equity.