January 5, 2015

Among the nauseating ed tech solicitations sent to my New York City Department of Education (NYCDOE) email account over the holiday was this message from New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio and family:

the people of the City of New York,

and our very best wishes to you and your family for

a New Year full of love, peace and happiness.

Bill, Chirlane, Chiara and Dante

Love, peace and happiness. I sometimes feel these emotions at school, but they are fleeting and occur only behind “closed doors,” in the presence of 25 six and seven-years-olds. I’m certainly not feeling any love or “sincere gratitude” from the NYCDOE administration, including the district in which I teach. But thank you, Bill, for the gesture. If ever you want to consult with working teachers and administrators who will tell you what our schools REALLY need in order to thrive, please reach out. Unfortunately, our prescription for education reform does not go along with the state and federal governments’ agendas, which, as it’s becoming increasingly evident, center on using teachers as scapegoats for the educational ills in our country.

I begin this new year with mixed emotions. I’m excited to resume the creative, inspiring work I do with my energetic first graders – we are a family – but I’m also weighed down with new feelings of self-doubt, indignation and increasing despair. Recent observations of my teaching practice, which are not holistic, have felt punitive. Charlotte Danielson’s Framework for Teaching – a rubric that addresses the so-called instructional shifts of the Common Core – is used as a checklist for these brief and infrequent snapshots of the work being done in my classroom. During this time, if administrators do not see evidence of what they are looking for – such as an assessment tied to an art project they are observing me teach – then I am at risk for a developing or ineffective rating for that component of the domain.

Additionally, New York’s use of valued-added modeling (VAM) to rate teachers, a tool widely considered to be junk science, is further demoralizing. Last year, I was rated “developing” on the local and state measures of New York’s fledgling teacher evaluation system; I still don’t know what standardized tests these ratings were based on since my English-language learners (ELLs) made progress on the 2014 NYS English as a Second Language Achievement Test (NYSESLAT). These Tweets from January 3, 2015 show that draconian teacher evaluation plans are not unique to New York. They make me want to cry.

On the first day of 2015, Carol Burris, principal of Long Island’s South Side High School, reported in The Washington Post’s Answer Sheet on the latest developments of New York’s teacher evaluation system. New York Board of Regents chancellor, Merryl Tisch, now wants 40% of teachers’ APPR (Annual Professional Performance Review) to be based on state test scores (it’s currently 20%).

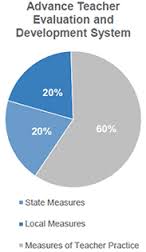

pie chart courtesy of the NYC Department of Education

According to Burris, here’s why Tisch is calling for this change to teacher accountability:

To Tisch’s dismay, APPR which she helped design, has not produced the results that she and Cuomo wanted; only 1 percent of teachers in New York State were rated ineffective in the most recent evaluation. The plan, according to the state’s Race to the Top application, was for 10 percent of all teachers to be found ineffective, with small numbers designated as highly effective. The curve of the sorting bell was not achieved.

In its latest blog post, the Port Jefferson Station Teachers Association (Long Island) highlighted this key point originally made by Burris:

Regardless of what 60%* of your evaluation says, if the growth score (test score) says you are ineffective, your entire rating will be ineffective. If you receive two ineffective ratings you will no longer be allowed to teach. *60% is based on observations (measures of teaching practice).

The above-mentioned state measures – growth scores – are based on student test scores from Pearson’s New York State Common Core assessments in English-language Arts (ELA) and math, which were first administered in New York in 2013. In receiving approximately $700 million in 2010 in Race to the Top funding, New York agreed to adopt the Common Core State Standards and to annually measure student progress toward “college and career readiness” as detailed in the new standards. PARCC and Smarter Balanced are two national consortiums that have also created Common Core-aligned assessments, however their tests are administered online. New York plans to transition to the costly PARCC online assessments. Here’s a description of Smarter Balanced:

The Smarter Balanced assessments are a key part of implementing the Common Core and preparing all students for success in college and careers. Administered online, these new assessments provide an academic check-up and are designed to give teachers and parents better information to help students succeed. Smarter Balanced assessments will replace existing tests in English and math for grades 3-8 and high school in the 2014-15 school year. Scores from the new assessments represent a realistic baseline that provides a more accurate indicator for teachers, students, and parents as they work to meet the rigorous demands of college and career readiness.

I detail these new testing initiatives because, contrary to what Common Core supporters argue, the Common Core State Standards are – by design – inextricably linked to Common Core-aligned assessments. The Common Core standards do not and cannot stand alone. They must exist in conjunction with aligned assessments in order to measure students’ “college and career readiness.” Student scores on these Common Core assessments are then used to hold teachers (and schools) accountable for using the Common Core standards to “prepare students for college and careers.” I have reported at length on the devastating impact these new Common Core tests have had on student learning and student morale in New York City schools.

Another reason I bring up the Common Core package (standards + curricula + assessments) is because there has been a recent lauding of and pining for New York’s “lost standards” in ELA and ESL which, with a relatively modest budget of $300,000, were written by state educators from 2007 to 2009. However, seduced by Race to the Top’s grant, in 2010 the Board of Regents abandoned the initiative and instead chained New York’s public schools to the Common Core. Lohud.com’s Gary Stern wrote about these “lost standards” in May 2014. Here’s a quote from the article:

“The Common Core was developed behind closed doors, but our New York standards were the work of extraordinary teachers and educators from the local level,” said Bonne August, provost of New York City College of Technology in Brooklyn, who co-chaired a committee that worked on the ELA/ESL standards. “We did things the right way, so teachers would buy in. Teachers are frustrated by the Common Core because they don’t see themselves in it.”

Lohud.com also created the below table to compare key features of the “lost standards” to the Common Core standards. As you can see, the Common Core came as a package, which included a testing program and a new teacher evaluation system. The “lost standards” did not. Unlike the “lost standards,” the Common Core is streamlined, making it easier to hold teachers accountable (via test scores and the Common Core-aligned Danielson Framework for Teaching). Furthermore, the adoption of the Common Core brought $700 million in funding to New York. The “lost standards” did not.

table courtesy of lohud.com

Chris Cerrone, a New York educator and school board member, wrote the following in a December 14, 2014 opinion piece for the New York State School Board Association (NYSSBA):

“How should New York proceed? We should drop the Common Core Standards and revive and continue the progress that created “lost standards,” known as the Regents Standards Review and Revision Initiative. The recent completion of the Social Studies Framework shows that quality standards can be created by New York educators who know their students, content, and age-appropriateness of curriculum.”

We teachers have an even bigger fight on our hands this year. If Andrew Cuomo and Merryl Tisch have their way, 40% of my rating will be based on measures determined by the state. I have no idea what they’ll use to assess first grade teachers, but I can assure you that any new NYS Common Core assessment that’s not teacher-created will be developmentally inappropriate.

One of my goals for the new year is to take a closer look at New York’s “lost standards” for ELA and ESL. Like Chris, I wish to make the argument that good work has already been done by educators in creating sound standards for our state. We should continue this work for the other content areas. Of the “lost standards,” Susan Polos, a highly regarded New York educator, was quoted by Gary Stern as saying, “Our standards were carefully and thoughtfully created, with educators involved, and should have survived.” I am not fond of standards (or rubrics), but I recognize the need for them.

I would also like to investigate alternative math standards. If I had the time, I’d create an entirely new math curriculum for first grade. GO Math!, which is Common Core-aligned, is a headache-inducing, poorly crafted math program that the NYCDOE adopted for its schools. If (when?) New York state abandons Common Core, we’d also have to propose a new assessment program and teacher evaluation plan. The working educators of New York know what’s best for our students. We need to reclaim public education in 2015.