The cover of the 11/3/14 issue of TIME Magazine blasts so-called bad teachers for being “rotten apples” and suggests that tech millionaires have figured out a way to get rid of them. However, what really stinks – among other ill-conceived corporate education reform initiatives – is the reliance on student test scores to measure teacher effectiveness. Once again, I wish to draw attention to the flaws of Advance, the New York City Department of Education’s new teacher evaluation and development system, which was implemented in 2013 in order to comply with New York State education law 3012-c. This 2010 legislation mandated an overhaul of the Annual Professional Review (APPR) for teachers and school leaders and introduced the current highly effective, effective, developing and ineffective rating system, a cornerstone of corporate education reform’s plan for teacher accountability.

The cover of the 11/3/14 issue of TIME Magazine blasts so-called bad teachers for being “rotten apples” and suggests that tech millionaires have figured out a way to get rid of them. However, what really stinks – among other ill-conceived corporate education reform initiatives – is the reliance on student test scores to measure teacher effectiveness. Once again, I wish to draw attention to the flaws of Advance, the New York City Department of Education’s new teacher evaluation and development system, which was implemented in 2013 in order to comply with New York State education law 3012-c. This 2010 legislation mandated an overhaul of the Annual Professional Review (APPR) for teachers and school leaders and introduced the current highly effective, effective, developing and ineffective rating system, a cornerstone of corporate education reform’s plan for teacher accountability.

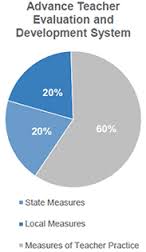

As the above NYCDOE pie chart shows, 20% of our overall teacher effectiveness rating comes from a local measure of student learning or MOSL (another 20% of our rating is based on a state measure such as the annual NYS Common Core ELA and math assessments).

Here is the NYCDOE’s definition of “local measure”:

- Local Measure – Recommended by a school committee appointed by the principal and UFT Chapter Chair and approved by the principal, each teacher’s local measure will be based on student growth on assessments and growth measures selected from a menu of approved options for each grade and subject (from the NYCDOE website).

My school chose the K-5 NYC Baseline Performance Tasks* in ELA and math as our local measure (MOSL). Students receive baseline scores for their performance on the fall assessments and will be tested again at the end of the school year to determine their growth in these two subject areas. While MOSL may no longer be an unfamiliar term to NYC parents, most have likely never set eyes on these performance tasks and may not realize how meaningless and labor intensive they are. *It is worth noting that in 2013-2014, these tests were called ‘assessments.’ They are now referred to as ‘tasks,’ but do not be fooled; they are still non-teacher created standardized tests.

Last month, it took me two and a half days to administer the 2014-2015 Grade 1 Math Inventory Baseline Performance Tasks to my students because the assessment had to be administered as individual interviews (NYCDOE words, not mine). The math inventory included 12 tasks, many of which were developmentally inappropriate. For example, in demonstrating their understanding of place value, first graders were asked to compare two 3-digit numbers using < , > and =. Students were also asked to solve addition and subtraction word problems within 100.

While I do not believe my students were emotionally scarred by this experience, they did lose two and a half days of instructional time and were tested on skills that they had not yet learned. It is no secret that NYC teachers and administrators view these MOSL tasks as a joke. Remember, they are for teacher rating purposes ONLY. “You want them to score low in the fall so that they’ll show growth in the spring,” is a common utterance in elementary school hallways. Also, there will be even more teaching-to-the-test as educators will want to ensure that their students are proficient in these skills before the administration of the spring assessment. Some of the first grade skills might be valid, but others are, arguably, not grade-level appropriate.

The Grade 1 ELA (English-language Arts) Informational Reading and Writing Baseline Performance Task took less time to administer (four periods only) but was equally senseless, and the texts we were given had us shaking our heads because they resembled third grade reading material. In theory, not necessarily practice, students were required to engage in a non-fiction read aloud and then independently read an informational text on the same topic. Afterwards, they had to sort through a barrage of text-based facts in order to select information that correctly answered the questions. On day one, the students had to complete a graphic organizer and on day two they were asked to write a paragraph on the topic. Drawing pictures to convey their understanding of the topic was also included in the assessment.

Not only are these “tasks” a waste of valuable instructional time, but at least six professional development sessions, which in theory are supposed to be teacher-designed, have been sacrificed to score them. The ELA rubric, in particular, was poorly written and confusing. It’s critical to note that these MOSL tests and rubrics were not created by working teachers. If they had been, they would have looked much different and the ELA rubric would have made sense. Sentiments ranging from incredulity to outrage have characterized our scoring sessions.

I suspect the majority of NYC public elementary schools selected these Baseline Performance Tasks as their MOSL option, however an alternative MOSL, which few know about, exists. Prior to the beginning of the 2014-2015 school year, 62 NYC schools, including The Earth School and Brooklyn New School, were chosen to participate in the Progressive Redesign Opportunity Schools for Excellence (PROSE) program, which – among other goals – satisfies the MOSL component of the NYC teacher evaluation and development system.

In her 10/27/14 weekly letter, Dyanthe Spielberg, principal at Manhattan’s The Neighborhood School (P.S. 363), wrote the following:

“Our PROSE plan modifies the MOSL (Measures of Student Learning) portions of the DOE teacher evaluation structure by substituting collected student work, observational data and narrative reports for MOSL. This process includes an emphasis on looking at student work, and reviewing informal and formal assessments. It requires ongoing reflective inquiry, as well as revisions of teacher plans and practice in relation to review of student work, data and feedback. Together, teachers will align criteria to create goals and assess progress. This collaboration, both with the grade level teams, other colleagues and parents, as well as partner schools, will allow teachers to conclude the year with a clear analysis of how they have grown as educators related to their actual performance in the classroom as opposed to a rating based on a student’s individual performance on an individual day. We are excited about this opportunity to practice and demonstrate how we think about assessment, teaching and learning, and to build on our partnerships with other NYC public progressive schools.”

Wow! Are they hiring? When a teacher friend told me about PROSE, I immediately became resentful and wished my school had participated in this program. Is anyone in Brooklyn’s District 19 even aware that PROSE exists? The NYCDOE, the UFT and even the Mayor’s Office claim that all NYC public schools were notified about the PROSE application process. I was on the School Leadership Team (SLT) last year and had no knowledge of it.

Charter schools aside, two public school systems within the NYCDOE appear to be evolving; one for NYC’s relatively affluent and well-educated population whose kids attend progressive schools that are given waivers to assess students outside of the Chancellor’s Regulations and the UFT contract, and the other for the masses. I have long felt that Tweed does not trust educators at Title I schools like mine and therefore feels obliged to micromanage us. Like second-hand clothing shipped off to Haiti, we are the ones who get the unpopular, but free, Core Curriculum, like ReadyGEN for ELA.

Education reformers, who saddled us with an excessive testing program and the Common Core, claim that their remedy – a very costly experiment – will close the achievement gap. But what about the widening quality of education gap? Are teachers to blame for bad curricula and assessments that they didn’t even create? Why should our ratings be based – in part – on poorly designed and often developmentally inappropriate tests that do not adequately reflect classroom instruction and students’ knowledge? Will TIME showcase this widely held viewpoint on a future magazine cover?